Axes#

In hist, a histogram is collection of Axis objects and a

storage. Based on boost-histogram’s

Axis, hist support six types of axis, Regular, Boolean, Variable, Integer, IntCategory

and StrCategory with additional names and labels.

Axis names#

Names are pretty useful for some histogramming shortcuts, thus greatly facilitate HEP’s studies. Note that the name is the identifier for an axis in a histogram and must be unique.

import hist

from hist import Hist

axis0 = hist.axis.Regular(10, -5, 5, overflow=False, underflow=False, name="A")

axis1 = hist.axis.Boolean(name="B")

axis2 = hist.axis.Variable(range(10), name="C")

axis3 = hist.axis.Integer(-5, 5, overflow=False, underflow=False, name="D")

axis4 = hist.axis.IntCategory(range(10), name="E")

axis5 = hist.axis.StrCategory(["T", "F"], name="F")

Histogram’s Axis#

Histogram is consisted with various axes, there are two ways to create a histogram, currently. You can either fill a histogram object with axes or add axes to a histogram object. You cannot add axes to an existing histogram. Note that to distinguish these two method, the second way has different axis type names (abbr.).

# fill the axes

h = Hist(axis0, axis1, axis2, axis3, axis4, axis5)

# add the axes using the shortcut method

h = (

Hist.new.Reg(10, -5, 5, overflow=False, underflow=False, name="A")

.Bool(name="B")

.Var(range(10), name="C")

.Int(-5, 5, overflow=False, underflow=False, name="D")

.IntCat(range(10), name="E")

.StrCat(["T", "F"], name="F")

.Double()

)

Hist adds a new flow=False shortcut to axes that take underflow and overflow.

AxesTuple is a new feature since boost-histogram 0.8.0, which provides you free access to axis properties in a histogram.

assert h.axes[0].name == axis0.name

assert h.axes[1].label == axis1.name # label will be returned as name if not provided

assert all(h.axes[2].widths == axis2.widths)

assert all(h.axes[3].edges == axis3.edges)

assert h.axes[4].metadata == axis4.metadata

assert all(h.axes[5].centers == axis5.centers)

Axis types#

There are several axis types to choose from.

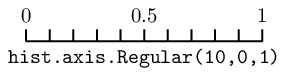

Regular axis#

- hist.axis.Regular(bins, start, stop, name, label, *, metadata='', underflow=True, overflow=True, circular=False, growth=False, transform=None)

The regular axis can have overflow and/or underflow bins (enabled by

default). It can also grow if growth=True is given. In general, you

should not mix options, as growing axis will already have the correct

flow bin settings. The exception is underflow=False, overflow=False, which

is quite useful together to make an axis with no flow bins at all.

There are some other useful axis types based on regular axis:

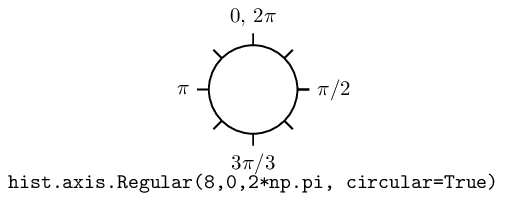

- hist.axis.Regular(..., circular=True)

This wraps around, so that out-of-range values map back into the valid range in a circular fashion.

Regular axis: Transforms#

Regular axes support transforms, as well; these are functions that convert from an external,

non-regular bin spacing to an internal, regularly spaced one. A transform is made of two functions,

a forward function, which converts external to internal (and for which the transform is usually named),

and a inverse function, which converts from the internal space back to the external space. If you

know the functional form of your spacing, you can get the benefits of a constant performance scaling

just like you would with a normal regular axis, rather than falling back to a variable axis and a poorer

scaling from the bin edge lookup required there.

You can define your own functions for transforms, see Transform. If you use compiled/numba functions, you can keep the high performance you would expect from a Regular axis. There are also several precompiled transforms:

- hist.axis.Regular(..., transform=hist.axis.transform.sqrt)

This is an axis with bins transformed by a sqrt.

- hist.axis.Regular(..., transform=hist.axis.transform.log)

Transformed by log.

- hist.axis.Regular(..., transform=hist.axis.transform.Power(v))

Transformed by a power (the argument is the power).

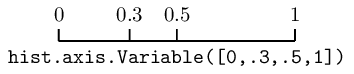

Variable axis#

- hist.axis.Variable([edge1, ..., ]name, label, *, metadata="", underflow=True, overflow=True, circular=False, growth=False)

You can set the bin edges explicitly with a variable axis. The options are mostly the same as the Regular axis.

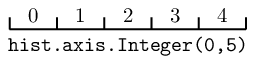

Integer axis#

- hist.axis.Integer(start, stop, name, label, *, metadata='', underflow=True, overflow=True, circular=False, growth=False)

This could be mimicked with a regular axis, but is simpler and slightly faster. Bins are whole integers only, so there is no need to specify the number of bins.

One common use for an integer axis could be a true/false axis:

bool_axis = hist.axis.Integer(0, 2, underflow=False, overflow=False)

Another could be for an IntEnum (Python 3 or backport) if the values are contiguous.

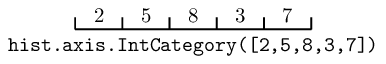

Category axis#

- hist.axis.IntCategory([value1, ..., ]name, label, metadata="", growth=False)

You should put integers in a category axis; but unlike an integer axis, the integers do not need to be adjacent.

One use for an IntCategory axis is for an IntEnum:

import enum

class MyEnum(enum.IntEnum):

a = 1

b = 5

my_enum_axis = hist.axis.IntEnum(list(MyEnum), underflow=False, overflow=False)

You can sort the Categorty axes via .sort() method:

h = Hist(

axis.IntCategory([3, 1, 2], label="Number"),

axis.StrCategory(["Teacher", "Police", "Artist"], label="Profession"),

)

# Sort Number axis increasing and Profession axis decreasing

h1 = h.sort("Number").sort("Profession", reverse=True)

- hist.axis.StrCategory([str1, ..., ]name, label, metadata="", growth=False)

You can put strings in a category axis as well. The fill method supports lists or arrays of strings to allow this to be filled.

Manipulating Axes#

Axes have a variety of methods and properties that are useful. When inside a histogram, you can also access

these directly on the hist.axes object, and they return a tuple of valid results. If the property or method

normally returns an array, the axes version returns a broadcasting-ready version in the output tuple.